The Great Outdoors is the greatest classroom

In quiet clearings across the front range of Colorado, groups of young children crouch under towering pines, dig in the soil, chase butterflies, and build forts from fallen branches. This is a forest school, a philosophical perspective towards learning outdoors that values holistic development.

The concept was originally developed in Scandinavia, specifically Denmark, during the 1950s and is part of a growing movement across America that trades traditional classrooms for the outdoors, where learning happens through independent play, exploration, and hands-on discovery.

Carly Gillbert perches on a rock at her office, Chautauqua Park in Boulder, Colorado, November 11, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Carly Gillbert perches on a rock at her office, Chautauqua Park in Boulder, Colorado, November 11, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Carly Gilbert’s first classroom smelled like dirt and pine needles, where learning meant flipping rocks to see what lived underneath. At five years old, while other kids practiced spelling under fluorescent lights, she traced letters in the dirt at her forest school, Green River. Every Friday, the class got to go hiking all over Boulder, Colorado, she jokingly called it a “tree-hugging school.” Yet her years under open sky were quietly shaping the teacher she’d become.

Decades later, she leads her kindergarten pod at Chautauqua, where the foothills double as chalkboards and backpacks thud into the dust, “This is my office, welcome to my classroom. …This is the dream job, I work at the Flatirons,” Gilbert raves.

Three students checking out the centipedes they caught in their "bug catcher" in Boulder, Colorado, November 9, 2025. (Izabelle-Stewart Adams CU News Corp).

Three students checking out the centipedes they caught in their "bug catcher" in Boulder, Colorado, November 9, 2025. (Izabelle-Stewart Adams CU News Corp).

From a young age, Carly Gilbert knew she wanted to be a teacher. While other kids experimented with different ambitions, her passion was unwavering — she was the child who taught her stuffed animals. Still, Gilbert envisioned more for herself than a traditional classroom of four walls. Gilbert wanted to teach in an office outside with the trees and the sun.

“I've always wanted to be like the real-life Ms. Frizzle and like to get a bus, renovate it into a classroom, and just take kids out into the woods and just be Ms. Frizzle. Like, that's the dream.”

Gilbert went to forest school until she was 12. Her mom was scared and confused about how her children would learn how to read and write while attending forest school. “She's like, my kids are never going to learn how to spell. They're just going to come home covered in dirt. … And I'm full circle going around and teaching forest school, and I'm getting a master's degree as well. … But as a product of a forest school, it just shows that you are capable of doing so much and being creative,” Gilbert recalls.

Carly Gilbert (third from the right) poses with her classmates from her forest kindergarten in Chautauqua Park. (Photo courtesy of Carly Gilbert).

Carly Gilbert (third from the right) poses with her classmates from her forest kindergarten in Chautauqua Park. (Photo courtesy of Carly Gilbert).

Now Gilbert went on the achieve a M.Ed. in Family Development and Educational Studies at the University of Colorado Denver. For her undergrad, Gilbert attended Knox College, where she got the opportunity to go to Denmark, the place where everything started. It was an incredible opportunity for Gilbert to “study abroad in one of the best education systems in the world.”

Being a student there showed her the power and purpose of nature learning, "These seven-year-olds built tree houses out in the woods [and] I was just like, this is what education is like. It is collaborative. It is mixed-aged. It is about community. It is about like survival, but in the most beautiful way.” She now prioritizes imaginative play and curiosity in her job teaching a Heartseed Wildschooling.

Shaylen Pergola beams as Heartseed students gather around for time on the blanket in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Shaylen Pergola beams as Heartseed students gather around for time on the blanket in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Heartseed Wildschooling, originally started in Louisville, Colorado, is a kindergarten and elementary forest school in Boulder County, founded by Shaylen Pergola in 2021. Her co-teacher is her partner, Hale O’Herren. They they feel it is important for kids to experience both masculine and feminine qualities in their teachers.

Hale O'Herren watches a Heartseed student as she reads the story she has been working on to the rest of her pod in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Hale O'Herren watches a Heartseed student as she reads the story she has been working on to the rest of her pod in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Pergola started Heartseed after a couple of years working in a classroom setting, teaching kindergarten and first grade at private schools across Boulder. She didn’t understand why someone would teach science indoors when there was a creek outside that kids could learn from in an interactive way.

“There was a need for kindergartens that didn’t want to go to indoor school, and their parents were fully on board with nature education,” Pergola said.

Heartseed started with four kids, three of them followed Pergola out of traditional learning, and now there are almost twenty kids.

Pergola shares how she pulls curriculum from her whole life experience, her time spent as a teacher, and in visits to other schools and nature-based programs. She also holds a BA in environmental studies and an MA in Learning, Developmental, and Family Sciences from the University of Colorado Denver.

Kids at Heartseed shed layers during free play in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Kids at Heartseed shed layers during free play in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Students break off to work on their fall stories during quiet time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Students break off to work on their fall stories during quiet time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young boy grabs a clipboard to work on his story in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young boy grabs a clipboard to work on his story in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

O'Herren helps a young boy with his schoolwork during quiet time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

O'Herren helps a young boy with his schoolwork during quiet time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

During free play, kids climb trees based on their capability in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

During free play, kids climb trees based on their capability in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young girl climbs on top of a log during free play in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young girl climbs on top of a log during free play in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Kids at Heartseed bring plenty of gear for any weather in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Kids at Heartseed bring plenty of gear for any weather in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young boy works alone on his fall story in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young boy works alone on his fall story in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A student leaves her gloves with other outdoor gear in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A student leaves her gloves with other outdoor gear in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Pergola is equipped everyday with learning supplies like books and markers in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Pergola is equipped everyday with learning supplies like books and markers in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

When it gets cold out or rains the kids hardly go inside whether it’s snowing or raining, cold or hot.

The school rejects the idea that when it’s rainy, you'd better stay inside, and when it’s cold, you might get sick. Instead, students are taught that such unfavorable conditions offer an opportunity to build resilience.

“When you take care of yourself as a teacher and are comfortable and setting a positive example,” Pergola said. “Then the kids also learn to enjoy the cold, enjoy the rain.”

Pergola says that when other kids may not want to play outside in foul weather, nature school kids simply don’t relate. They are dressed for the occasion and comfortable in the weather so they can enjoy their day at nature school.

Pergola hopes to instill values of resilience, physical and social confidence, uniqueness, social-emotional skills like empathy, and connections with each other and the natural world.

“We focus on relationship-based learning,” Pergola said. “Relationship with each other and with nature, and fostering a love for learning and love for nature that will last their whole lives. The idea is that they grow into adults who care for the Earth.”

The day starts with morning math on the blanket. Every kid is on a different level, which means everyone gets individualized instruction time. Then comes morning rituals and songs, specifically Waldorf songs. Next is a 30-minute hike to the creek, where they spend the rest of the day. When they first arrive at the creek, they do a safety assessment of the environment: “Is the water really high or really fast? Is it windy?”

Social-emotional time is when the kids practice building emotional literacy and emotional vocabulary to talk about “our feelings and take care of ourselves and others,” Pergola said. Following is when kids get to participate in a fully self-led free play, exploring, and learning through nature in imaginative exploration.

Pergola says, “[It] is actually one of the most important parts of our day for learning, because through all of their cooperation and teamwork and engaging with their friends… they get to come up against challenges…and solve problems and really learn hands-on on engaging with the natural world and with each other.”

Language arts of literacy, poems, reading, and writing follow, and when lunch ends, everyone walks back, does a closing circle, and sings a goodbye song to share gratitudes of the day.

Shaylen Pergola, the founder, shares the story of Heartseed Wildschooling in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Homeschool mothers found the forest school Heartseed, wanting an alternative learning environment for their young children. One mother, Nicole Shelley, moved to Colorado from Southern California and immediately placed her children in a forest school after gaining inspiration from the book “Nature Fix,” by Florence Williams.

“That book talks about the benefits of being outside and learning outside, and that's basically what we wanted as well,” she said.

Shelley appreciates the closeness among the parents and families of the nature learning community. The small cohort of kids has been in forest school together for a while, and even when not in school, they all hang out on the weekends and will spend hours running outside playing with each other.

“To me, it seems like all the families, they all really value time as a family unit together,” said Shelley, “[in traditional schools] it’s just school life and then home life,” a separation she feels can make it harder for parents to really understand their children’s day-to-day experiences.

Shelley started homeschooling because she wanted the freedom to be able to teach her daughter any subject at any time. They often travel and make a lesson out of the activities their adventures. When they went to South Dakota with friends, they were hiking, learning about the history and creation of the waterfalls they were seeing.

“Just being able to make that into a lesson while traveling … I don’t think you would normally be able to learn that in just a traditional school.”

Heartseed kids climb and build tree forts during play time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Heartseed kids climb and build tree forts during play time in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Shelley isn’t sure about when and if there will be a transition for her seven-year-old to go into classroom learning at a private or public school. She prioritizes letting her kids pick their academic material at home, but also their own path, so she is waiting to see as her kids get older if they will stay homeschool or go into traditional classrooms.

Overall, Pergola feels grateful every day to be outside in beautiful Colorado and to see kids grow into themselves. A challenge is the lack of hesitation by the general public, “[there is a] lack of understanding,” says Pergola. She shares how it can be hard to talk about forest schools and encourages people to join the movement because some people are simply apprehensive.

Yet teachers like Gilbert push back in unique ways. When Gilbert's students found a caterpillar hiking and moved it off the trail to be safe from human shoes, she called them planet protectors. She hopes to foster the minds and hearts of the next environmental stewards.

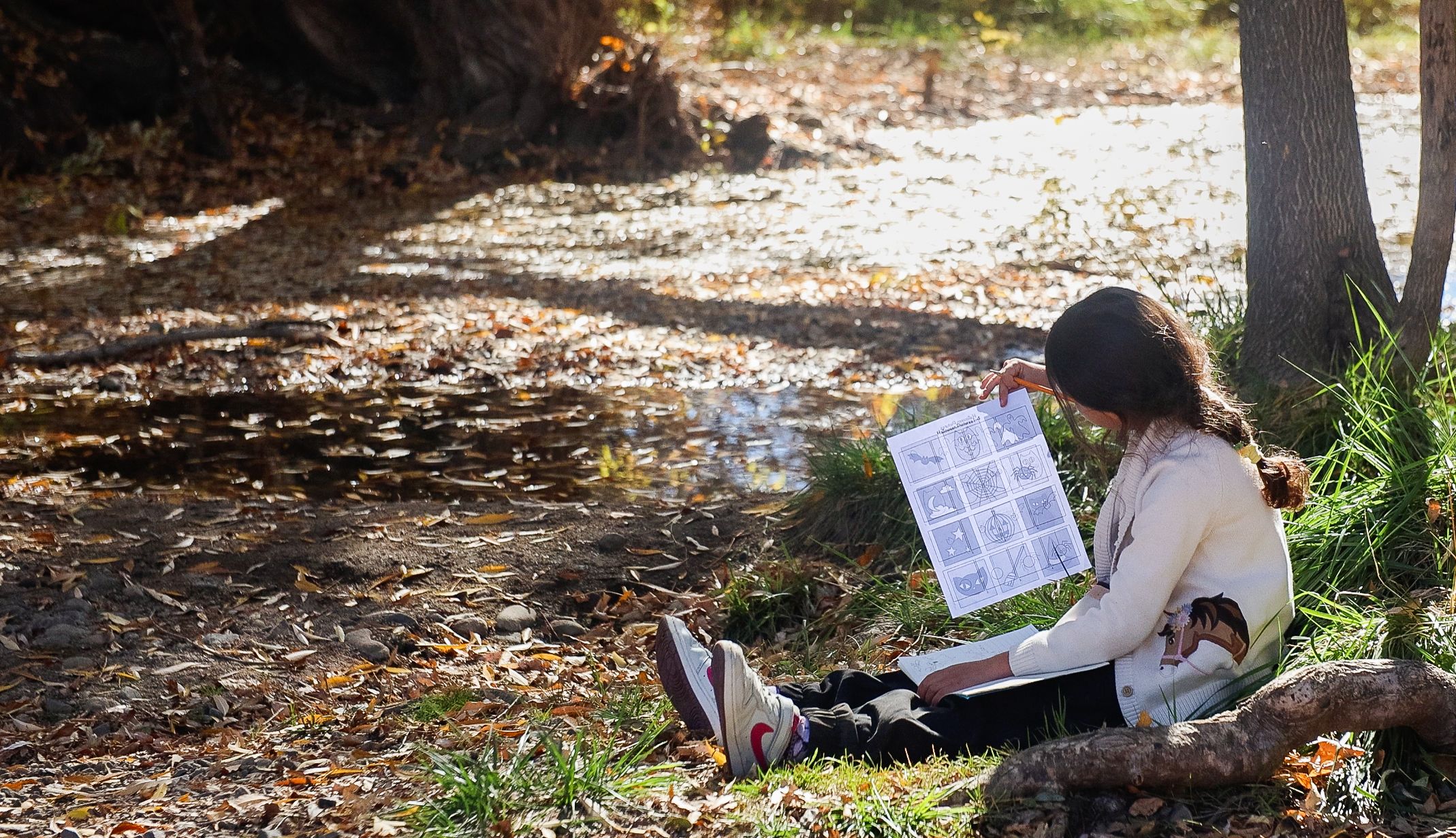

A young girl works on a Halloween worksheet next to the creek in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young girl works on a Halloween worksheet next to the creek in Louisville, Colorado, October 29, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Gilbert is also an advocate for making forest schools as equitable as they can be. For her chapter of Heartseed, government funding allows students to come to forest school one day a week for free. According to Private School Review, the average private elementary school tuition in Colorado is $13,216 per year in 2025-26, according to Private School Review.

Like Pergola, forest schooling is more than a job. For Gilbert, it’s a lifelong loop back to the girl who once learned reading, writing, and wandering under a canopy of pines. And as she looks ahead, her vision for education remains rooted in that same sense of wonder and possibility.

A young boy leaps from a rock in Chautauqua Park in Boulder, Colorado, November 9, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A young boy leaps from a rock in Chautauqua Park in Boulder, Colorado, November 9, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Educators like Gilbert and Pergola hope for a future where forest schools can be made available to families across the state. Brett Dabb, the founder and director of Colorado Nature School based in Golden and Indian Hills, Colorado, is currently advocating for such accessibility.

While forest schools typically host small pods of children, Dabb wishes nature education becomes more mainstream in the next few years. While forest schools have grown in popularity in the past decade, the issue of accessibility for all families to enroll their children creates an obstacle in affordability.

Brett Dabb, founder of Colorado Nature School in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Most forest schools in Colorado are privately owned and require that parents pay a tuition to enroll their children. Dabb is currently working with the state to get financial support for these programs through Universal Preschool (UPK) and Childcare Assistance Program (CCAP) funds.

“This is such a beneficial approach to early learning and development for young kids that it should be mainstreamed,” Dabb said.

Forest school tuition can range from program to program, and families sending their kids to the Colorado Nature School pay a tuition of $1,500 a month for a five-day program. Dabb hopes that with the state backing these programs, more families will be able to access it freely, and more dedicated educators will be able to start these schools throughout the state of Colorado. “We’ll see what the rules and regulations end up with,” Dabb said, “I’m always a little weary about that.” Dabb remains unsure about obstacles navigating funding in its early stages, but holds hope for the future of forest school availability.

Dabb’s program of three to five-year-olds are greated with cool November air as they walk through Lookout Mountain Nature Preserve. Forest school has just begun, and the children lead their guides to whatever clearing caters to their play-based desires for that day. As they reach a small clearing, Dabb leaves the children to frolic around the area while he leans up against a tree and observes the intellectual and emotional growth that happens around him.

In his passion for early childhood education, Dabb earned his master’s degree in early childhood administration, leadership and policy, and fell in love with nature-based learning while serving the Peace Corps in South Africa.

“My journey that brought me to nature-based learning as an adult definitely started when I was a kid,” Dabb said. “I was playing outside and learning all the time through exploring my backyard in the woods and beyond with friends, and sometimes alone. In those formative years of just being able to explore without an adult supervising … was really important to me.”

Dabb carries this ideology in his own school, as once they arrive at their chosen learning area, the kids run about the area, having no instruction other than to be themselves in everything they do. Snacks and lunches are not scheduled, as Dabb and his fellow guides encourage the children to listen to their bodies, and eat whenever they feel hungry. “Look what I have Mr. Brett,” a student says as she enjoys her snack at her own leisure. These kids call the shots as they act out their imaginations during school, and come home excited to share what they have done with their parents.

Dabb finds that the parents who seek out his program value a similar idea of expanding their children’s understanding through recreation and investigation. “Autonomous, independent, nature-based learning and exploration often sits as a family ethos for a lot of the folks that find us,” Dabb said.

According to Dabb, families enrolled in the program thrive when playing at home, and develop a strength that would otherwise be lacking in students who learn indoors. “They’ve got the rest of their lives to sit at a desk in a classroom,” Dabb said.

Two students holding hands at Colorado Nature School in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Two students holding hands at Colorado Nature School in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Colorado Nature School's classroom in Louisville, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Colorado Nature School's classroom in Louisville, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Young girl is climbing a fallen tree in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Young girl is climbing a fallen tree in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Tree play structure at Colorado Nature School in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Tree play structure at Colorado Nature School in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

A young boy is playing with the Earth in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

A young boy is playing with the Earth in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Students at Colorado Nature School sitting on a log in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Students at Colorado Nature School sitting on a log in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

A young boy with his school materials in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

A young boy with his school materials in Golden, Colorado, November 10, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

The parents behind the growing movement of forest schools hold firm in their belief that outdoor education provides so many more opportunities for their children.

For Eric Reigler, he had the opportunity to admit his eight-year-old son in the program he started back in 2019. Reigler, a single dad, enrolled his son at the age of two after teaching in a public school, wanting something different for his child. It’s a bring your kid to work day every day at Wonders of Nature Forest School in Palmer City, Colorado.

Eric Reigler, founder of Wonders of Nature Forest School, stands in the woods where class takes place in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Eric Reigler, founder of Wonders of Nature Forest School, stands in the woods where class takes place in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

It’s a perfect day at the office. The air is crisp, leaves scatter across the ground, and the creek hums at a steady rhythm. On his way in, Reigler even snagged a fresh apple. But Reigler’s office isn’t lined with cubicles or desks — it’s the forests of Glen Park. Instead of a computer, he carries a large green water canister.

He walks with his 30 students between the ages of three to five all day in the woods, stopping to let them admire the wild mushrooms and collect rocks. The hike to the classroom with no walls is steep and unmarked. It leads to a clearing where you can find a plateau with handmade tree dens and floors littered with pinecones.

The day begins with morning circle, a daily ritual.

“Morning circle is sort of our introduction for the day,” Reigler explained. “Our first 30 minutes is usually free play … then we’ll do yoga, introduce our topic, and give every kid a chance to speak. It all follows the seasons.”

A tree fort built by kids at Wonders of Nature in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

A tree fort built by kids at Wonders of Nature in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

During October, students are making insects out of sticks, autumn leaves, and pine needles. They have a chance to plan their own schedule such as when they eat and are allowed to climb trees if they please. Reigler teaches them how to identify safe branches while reminding them that the choice is theirs and that if they climb up, they’re strong enough to climb back down.

“Our goal is to let them be kids. We don’t have silly rules like, ‘Sit down and be quiet.’ It’s time to throw rocks and play in the creek.” Reigler said, adding, “If you climb a tree, you’re strong enough to climb down. That’s part of teaching independence.”

This approach is important in what Reigler describes as a strong interest of parents looking for a natural environment for their angsty sons.

“We see it with a lot of little boys that have a lot of energy and are forced into sitting in a classroom for seven hours a day,” he says. “And for three, four, five, six-year-old boys, most of them are not comfortable sitting down in a chair for the day. We were meant to move.”

A tree fort built by Wonders of Nature kids in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

A tree fort built by Wonders of Nature kids in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Reigler's water canister that must last him the entire day in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Reigler's water canister that must last him the entire day in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Reigler lists activities of the day in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Reigler lists activities of the day in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

The Glen Park sign that welcomes students as they are dropped off at school in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

The Glen Park sign that welcomes students as they are dropped off at school in Palmer City, Colorado, September 30, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams, CU News Corps).

Most of the families who join forest schools are looking for a different fit for their energetic children who struggle in conventional classrooms, especially at young ages.

“Kids don’t need to be learning letters and numbers before six. What’s more important is that they develop independence and curiosity,” Reigler said. He’s noticed that interest in the school has surged in recent years, almost doubled. Families find his forest school themselves as Reigler does no advertising despite having a waitlist, just word-of-mouth.

Reigler says the children don’t just explore the forest, they build a sense of ownership while a sense of toughness and resilience is central to the school’s philosophy. “We talk about doing something hard every day,” Reigler said.

When storms roll in, it becomes a lesson. Recently, his older group set up a tarp shelter during a hailstorm, practicing the knots they’d been learning. These students also whittle sticks, start fires with flint and steel, and carry their own ropes to master new knots each week. But the skills aren’t only physical.

“I think it's important for kids to develop independence and autonomy and not necessarily wait around for the next direction. So we often see that with other kids that come from traditional education is that they’re waiting for somebody to tell them how to play or tell them how to learn. And our kids are doing that on their own. And so it’s kind of the benefit that I see.”

Students also practice teamwork by maintaining rock shelters and forts year-round, repairing them together on return visits. They also build a sense of environmental stewardship, correcting each other if trash falls or reminding one another to treat plants gently.

“They see it as their responsibility to take care of our planet,” Reigler said. Instilling climate resilience in the younger generation is exactly what forest school and Reigler's practice intends.

In the future of Nature Wonders School, Reigler closed on three acres of land that will host kindergarten through 18 on the same “campus.” Similar to the Sudbury Valley model, it is all about mixing ages and the curriculum is inquiry-based. “Kids learn best from other kids that are two to three years older than them. They’re kind of in the zone of proximal development. So it's kind of our idea.”

Jackie Trapp explains why forest school was the best program for her son, Ryder in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Miles away from Reigler’s school is a teacher at Boulder Jewish Community Center (JCC), Colorado, Jackie Trapp. Her four-year-old son, Ryder, is enrolled in a nature preschool where she works.

The student walks through the woods with two of his fellow classmates, following their guide, while observing the land around them. The group approaches a small secluded creek, and Ryder, wearing a red stocking cap and rain boots, jumps onto a small rocky island with a large stick in hand. He pretends he is on a boat, using the stick as his paddle, and his two friends as shipmates. Each has their own destination, but they all work together.

JCC kids pretend they are on a boat as they paddle through the creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

JCC kids pretend they are on a boat as they paddle through the creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

“Just seeing [him] outside, it’s just a night and day experience from anything that [he’s] getting inside,” Trapp said.

Working in the forest school program is what led Trapp to enroll her own son when he reached preschool age. “When he was two, I was like, ‘Oh, this kid is not cut out for forest school,’” Trapp said. But Trapp saw a change in Ryder as he got older and allowed him to take part in the outdoor program. Seeing him gain an entirely new perspective on the world outside gives Trapp a sense of fulfillment as she watches her son explore the outside.

“It’s just really cool to see him … thriving out there,” Trapp said.

Working at the JCC, Trapp is able to watch her son prosper during school hours, but she has also noticed Ryder bringing what he’s learned home with him as they explore nature on the weekends. “We live close to a creek and a park, and we spend a lot of time in nature … and he’s got a lot of really cool ideas that come out of forest school.”

Mattie Schuler and JCC kids inspect a bug while walking to the creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Mattie Schuler and JCC kids inspect a bug while walking to the creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Though Ryder is in his last year of forest school, Trapp believes that what he has learned in his time outside will set him apart from other kids as he enters the public school system.

“I want him to spend as much time as he can out there, and having fun before … public school is a whole different ball game.” Even on days when Ryder does not want to play outside, Trapp reminds him of how different school next year will be, and how valuable his time outside will seem once he begins learning within four walls.

Ryder’s opportunity for outdoor education came about thanks to the school’s founder, Mattie Schuler.

The sounds of chickens clucking and goats bleating greet Schuler as she begins another day of running forest school in Boulder. As she approaches, kids greet her as they run towards the creek and create potions in the mud kitchen. The smell of wood burning in the distance adds a bit of warmth to a crisp autumn morning.

Mattie Schuler, the founder of the JCC's forest school program in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Mattie Schuler, the founder of the JCC's forest school program in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Schuler founded the JCC’s forest school program in 2019. While the center already had an indoor preschool program, Schuler believed that incorporating a more nature-based curriculum for young children could help to encourage imagination and outdoor play.

“In 2015 I went to grad school, and my capstone and focus was on nature play with little kids,” Schuler said. Discovering this new type of schooling opened doors for Schuler and showed her how well kids can adjust to outdoor learning.

One day, Schuler recalls as monumental in her journey toward opening a forest school happened while teaching in a standard classroom setting. “There was a moment where a big tree branch fell on our playground,” Schuler said. While her colleagues tried to quickly remove the obstacle, deeming it dangerous, Schuler told them to wait and watch the kids as they began to play on it. “It was so amazing. It was this moment where these little toddlers are like, ‘I’m climbing a tree, I’m in a tree house.’”

Schuler realized what creating a forest school could do for so many young children with active imaginations and loads of energy. “I just remember that moment was so special for me,” Schuler said. “Everybody’s kind of going to be like, ‘Oh, we have to remove this maybe unsafe thing.’”

Forest school takes place on what the staff call “The Land.” Kids play how they want to on a field not far from the indoor learning center of the JCC. During free play time, students run about this area, letting nothing but their imaginations guide them. They climb in the trees surrounding the land and pretend to be paddling on boats as they skip through the creek. Through independent play, these kids are able to discover many of the hidden gems nature has to offer.

“We talk a lot about bugs and birding, and wildlife, and leave no trace,” Schuler said.

Backpacks are lined up on the land as kids explore the nearby creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Backpacks are lined up on the land as kids explore the nearby creek in Boulder, Colorado, November 3, 2025. (Izabelle Stewart-Adams CU NewsCorp).

Schuler finds that many of the kids in her program are able to develop more awareness of the environment around them as they explore everything the land has to offer.

“Their ecological awareness is something that we really try to grow, but with just playing outside every day, it just kind of grows naturally,” Schuler said.